NCPC has served as the federal government’s planning agency for 100 years. It was also the city’s local planning agency until 1974. The agency has aspired to preserve and enhance the design of our nation’s capital to reflect democratic ideals of openness and participation while also meeting the needs of people who live, work, and visit here.

Through a range of events and resources, NCPC’s 2024 Centennial presents an opportunity to celebrate the history of planning in Washington and the region, acknowledge unfairness in past planning practices, and consider lessons learned for planning the capital’s future.

About NCPC

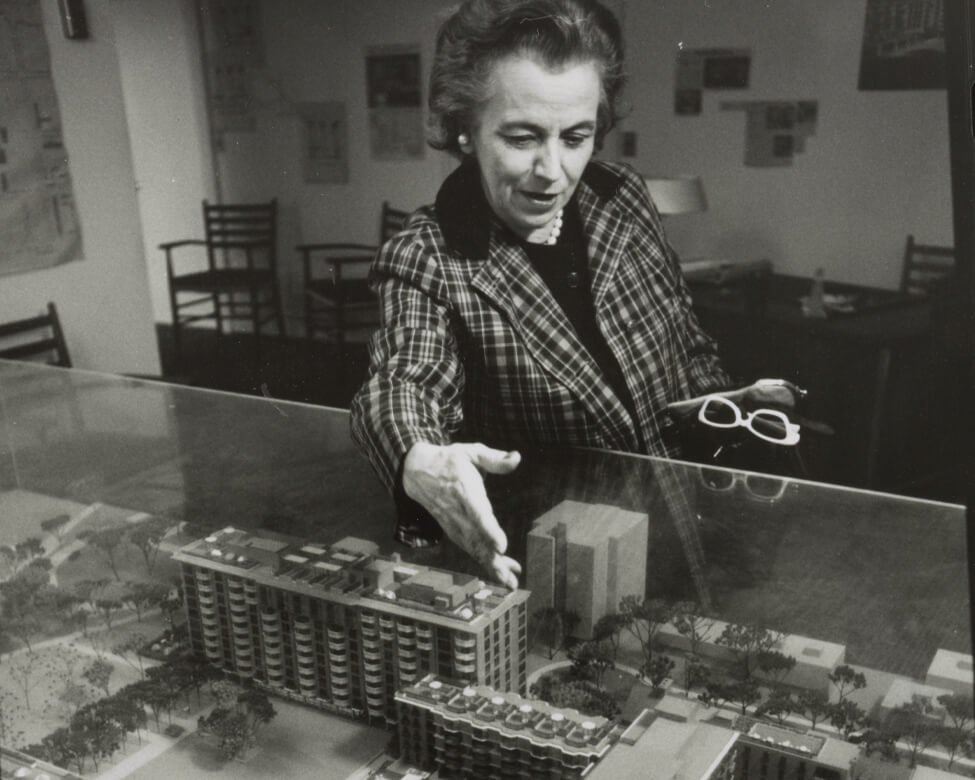

– Elizabeth "Libby" Rowe, NCPC Chair, 1961-1968

-

1924

January 16th, 2014Congress establishes the National Capital Park Commission to acquire land for public parks, parkways, and playgrounds in Washington and jurisdictions in Maryland and Virginia.

-

1926

February 28th, 2014Congress grants the agency, renamed the National Capital Park and Planning Commission, broad planning authority for highways, housing, parks, sewers, subdivisions, and more for both the federal government and local residents.

-

1952

March 20th, 2014Congress renames the agency to the current National Capital Planning Commission. It formalizes NCPC as Washington’s central planning agency, with planning responsibilities for the federal and local city.

-

1973

May 20th, 2014The District of Columbia Home Rule Act hands local planning to an elected mayor. NCPC continues to this day to plan and review proposals for developing federal properties in Washington and the region, and certain District properties.

-

2024

July 9th, 2014NCPC celebrates its Centennial and looks toward another century of planning for the National Capital Region.

-

2025+

July 9th, 2014NCPC will continue to serve as the federal government's planning agency, protecting the historic nature of the city while advancing plans and policies that will have a positive impact of the National Capital Region.

NCPC created this exhibit with technical support from Prologue DC. This digital exhibit is a companion to a physical exhibit on display at the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library from June 6 – September 1, 2024, as well as other DC Public Libraries and regional locations throughout 2024. NCPC extends its appreciation to the DC Public Library for its generous assistance and support and thanks the advisors who contributed their expertise.

Planning History

-

Pre-1600s

Before There Was a City

Long before it becomes Washington, DC, this land is home to Indigenous people known as Nacotchtank or Anacostans. They hunt, fish, quarry stone, and trade at the confluence of the Anacostia and Potomac Rivers for thousands of years. In the 1600s, European settlers take their land for farming and bring diseases that kill them. Indigenous people from different nations remain in the region today.

-

1790-1792

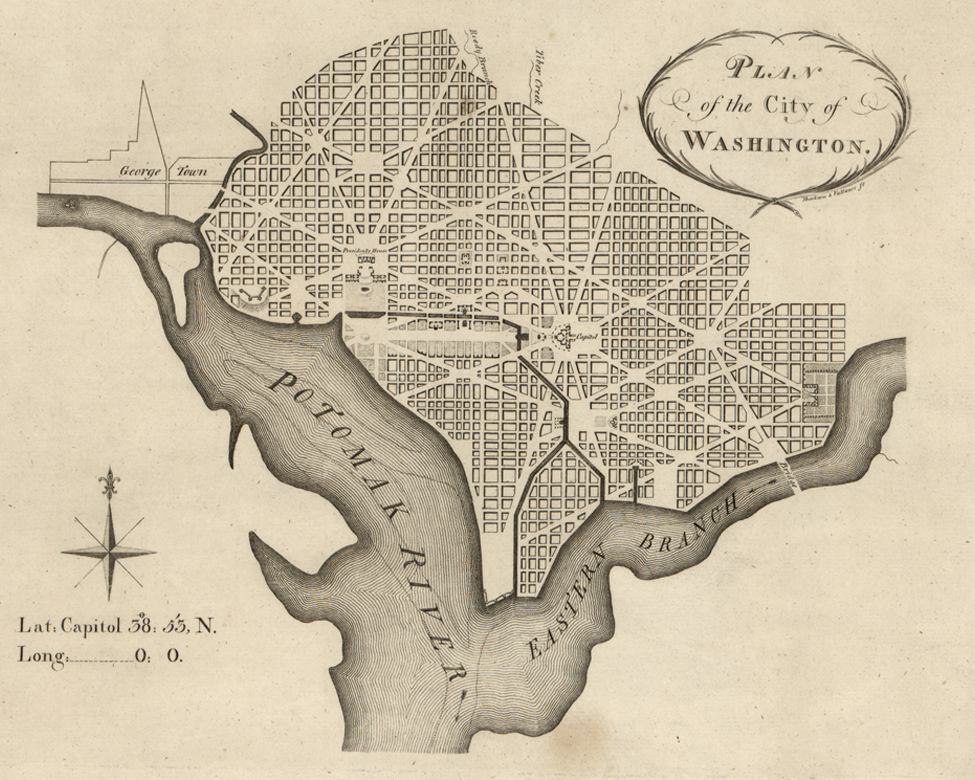

The L’Enfant and Ellicott Plans

President George Washington chooses the land for the nation’s capital in 1790. His wartime assistant, engineer Pierre L’Enfant, draws up a plan for the new city of Washington. L’Enfant’s visionary design, which includes many parks, places key civic buildings on higher ground, connects them with grand avenues, and creates long, sweeping views. L’Enfant designs the city to represent the young country’s democratic ideals. For example, he uses Pennsylvania Avenue to link the White House and the U.S. Capitol, two of the three branches of government.

-

1901-1902

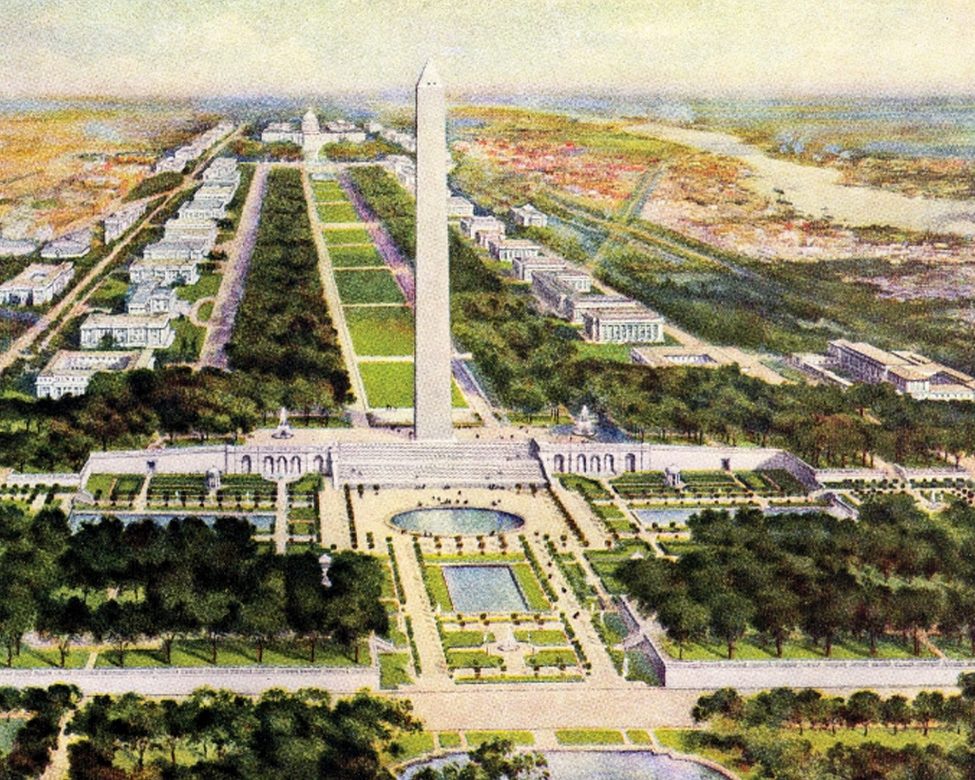

The McMillan Commission Plan

As the city grows through the 1800s, development veers from L’Enfant’s plan. The 1901 Senate establishes a commission, led by Senator James McMillan, to restore and give new meaning to L’Enfant’s vision of a beautiful and inspiring capital. The National Mall’s open greenway, the city’s public park and open space system, and the grand neo-classical buildings that characterize Washington’s federal core would result from the McMillan Plan.

At the turn of the 20th century, the National Mall looks very different from today. Stands of trees and winding paths are in the foreground, while a train station and tracks are located closer to the U.S. Capitol.

-

1910

The Height of Buildings Act

The 1910 federal Height of Buildings Act limits building heights across the city. Over time, this restriction shapes development and results in Washington’s distinctive, low skyline.

The 1894 construction of the Cairo luxury apartment building prompts concerns about design and fire safety, leading to the Height of Buildings Act.

Heights & Views -

1924

– Washington: City and Capital (1937)

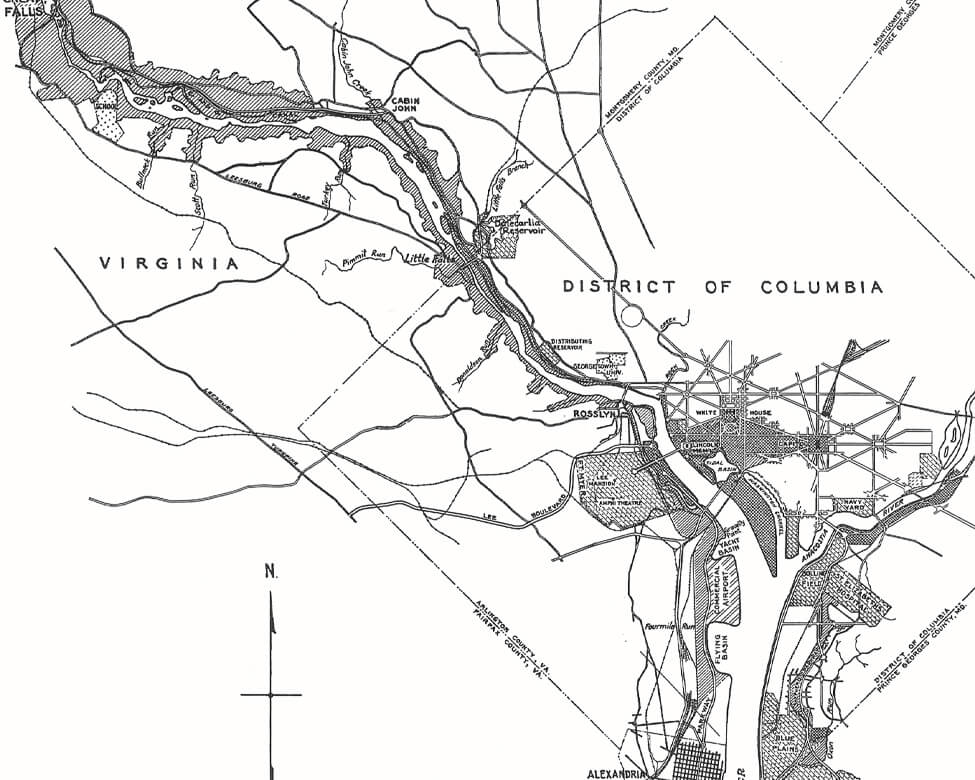

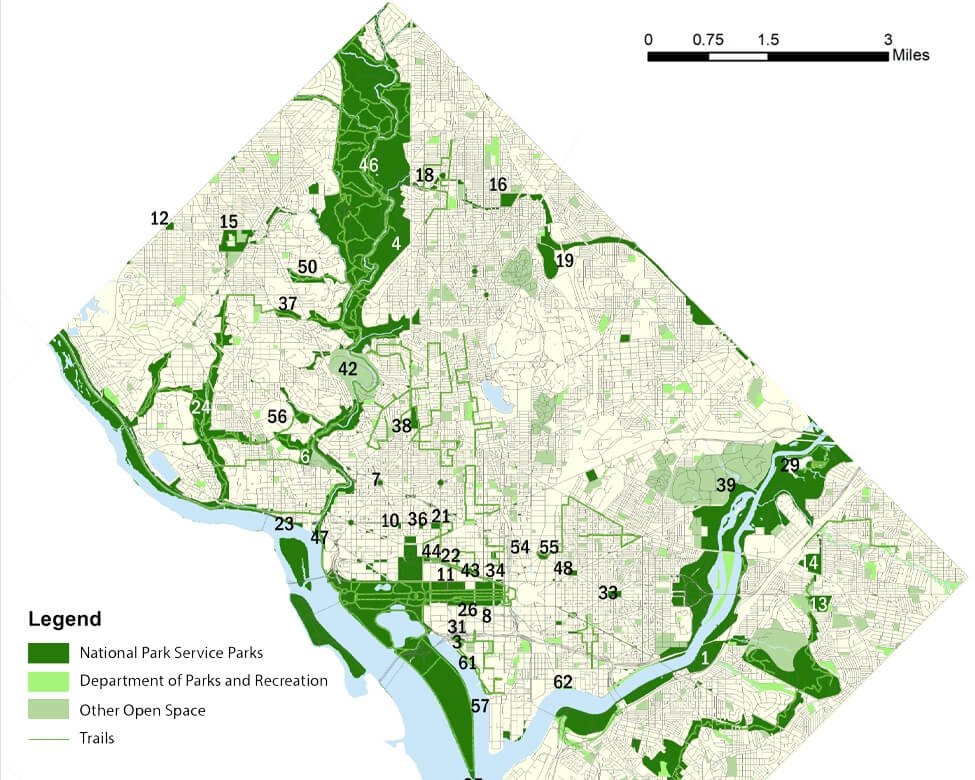

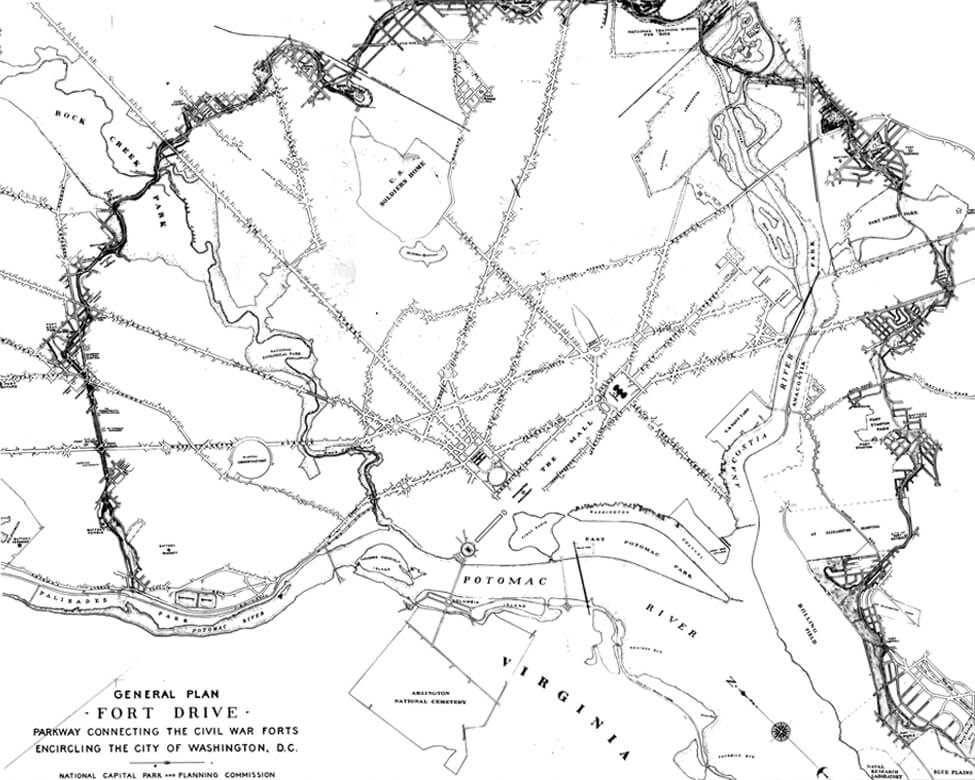

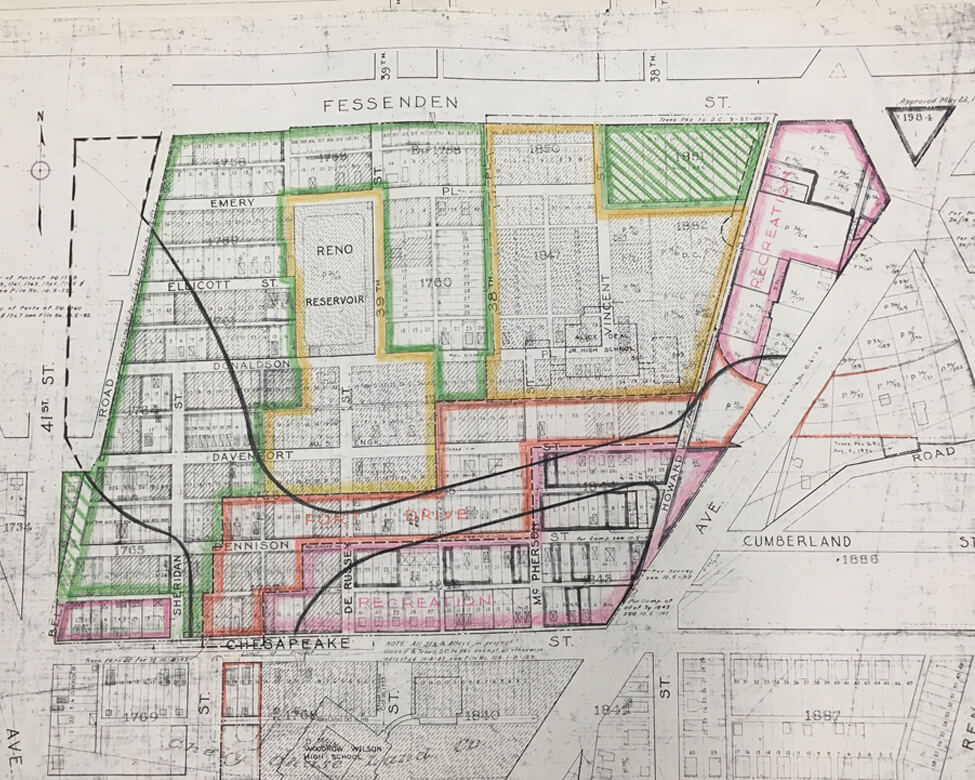

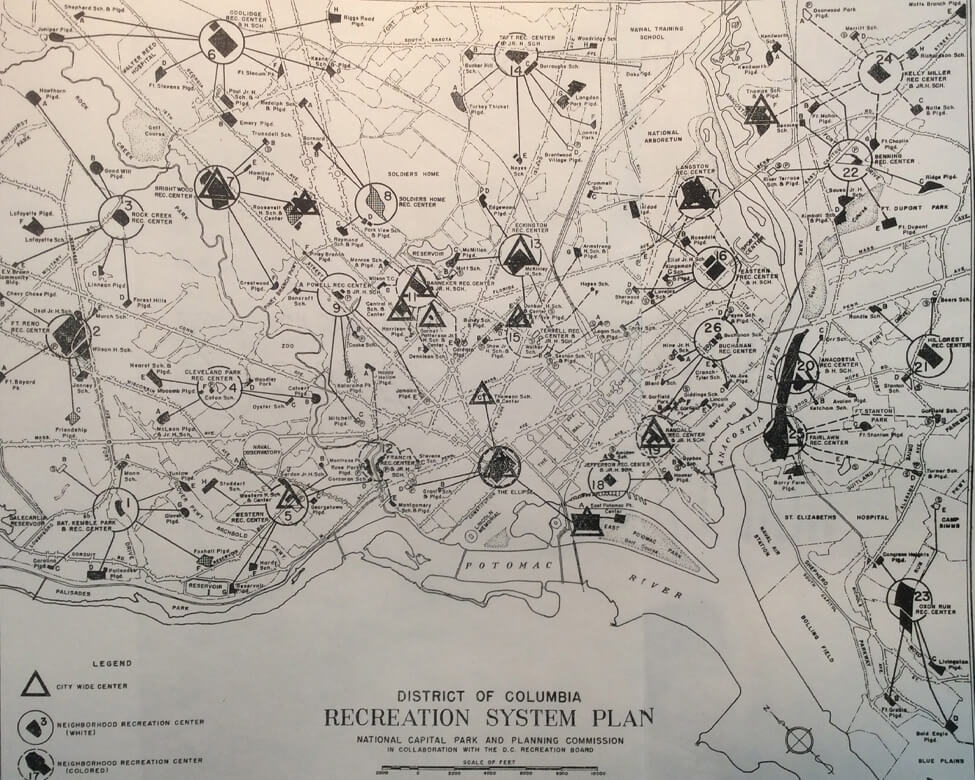

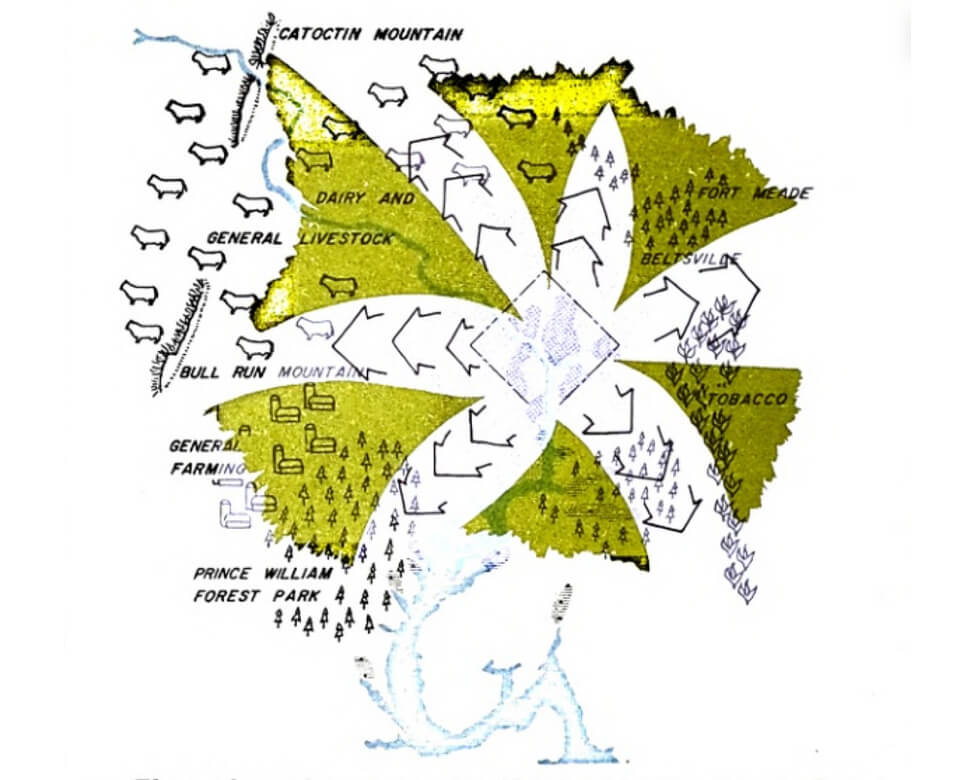

After World War I, civic groups worried that development was filling open land, ruining forests, and harming water quality. NCPC was established in 1924 to plan parks, protect natural resources, and fulfill the ambitious McMillan Plan. Under the 1930 Capper-Cramton Act, the agency bought land to extend Anacostia and Rock Creek Parks and for parkways along the Potomac River in Virginia and Maryland.

Capper-Cramton Act Parks and Open Space

– Phylicia Fauntleroy Bowman, who grew up in Petworth in the 1950s.

More About Reno City

– Washington: City and Capital (1937)

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

In the 1930s, the Federal Triangle displaces working-class

neighborhoods, including Washington’s first Chinatown. This is a

view of an industrial section of the old neighborhood.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

In the early 1940s, Pentagon construction destroys a historic Black

community known

as

Queen City (or East Arlington), seen above, whose residents are

given

only weeks to

vacate their homes.

National Archives

National Archives

In 1933, many federal employees park in this Federal Triangle lot,

now

filled by the Ronald Reagan Building and International Trade Center.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Federal Bureau of Investigation clerks at work in the Justice

Department

building in 1956.

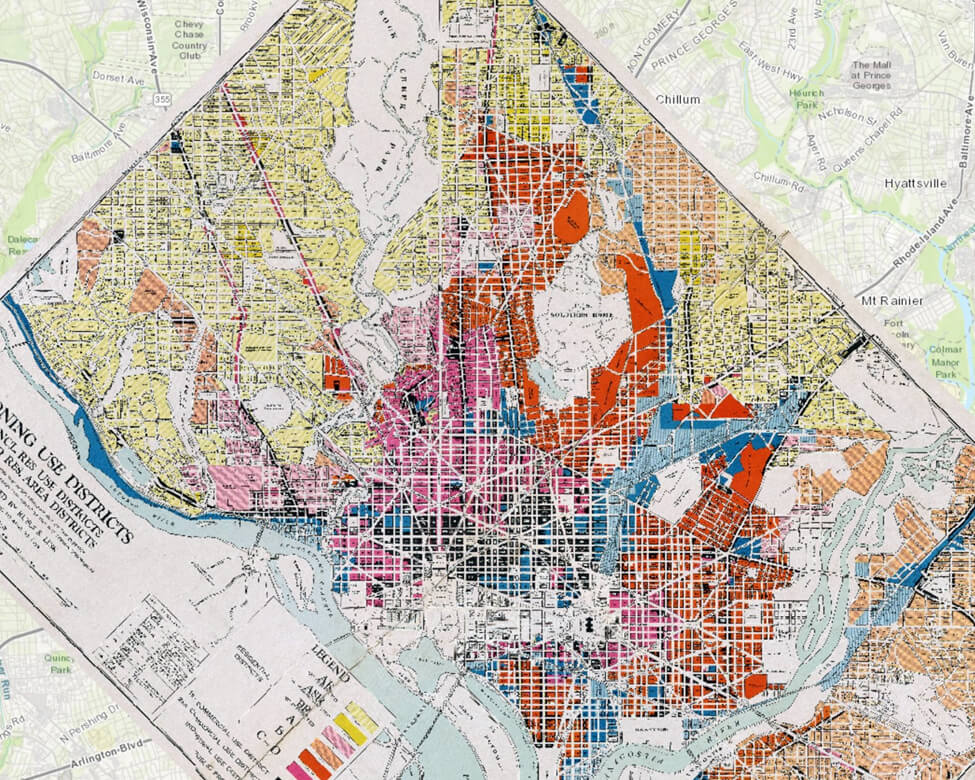

With the 1945 District of Columbia Redevelopment Act, Congress directed NCPC to write Washington’s first “comp plan.” The agency hired St. Louis-based Harland Bartholomew for the job. In the 1920s, Bartholomew had created Washington’s first zoning map and a transportation plan that proposed widening and adding roads throughout the city. He also helped plan the nation’s Interstate Highway System.

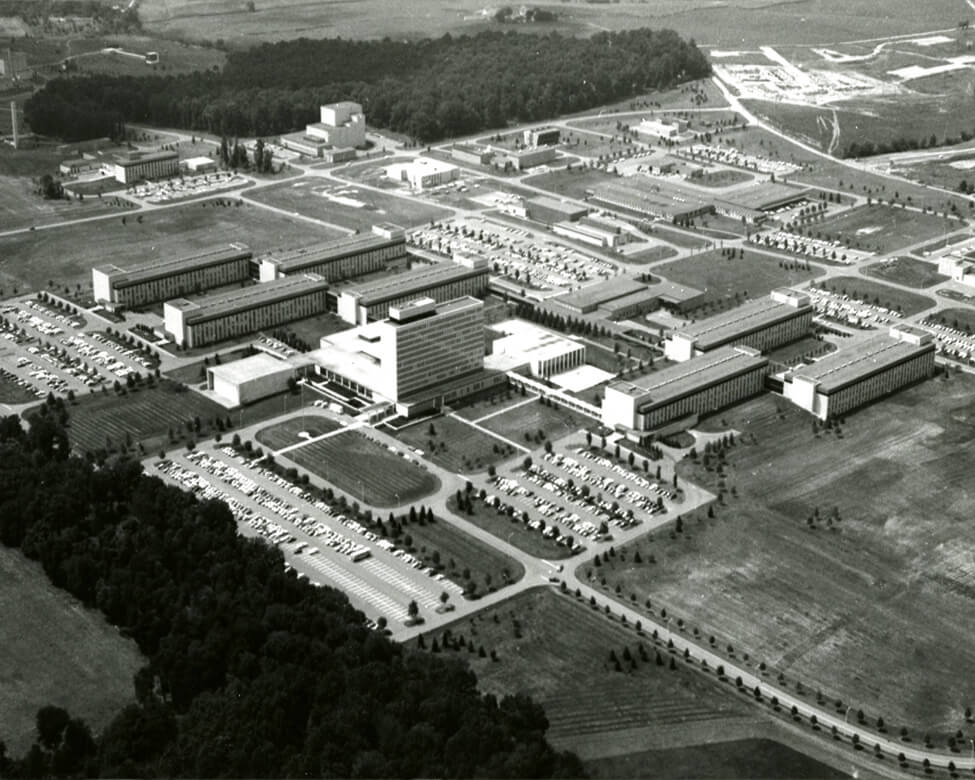

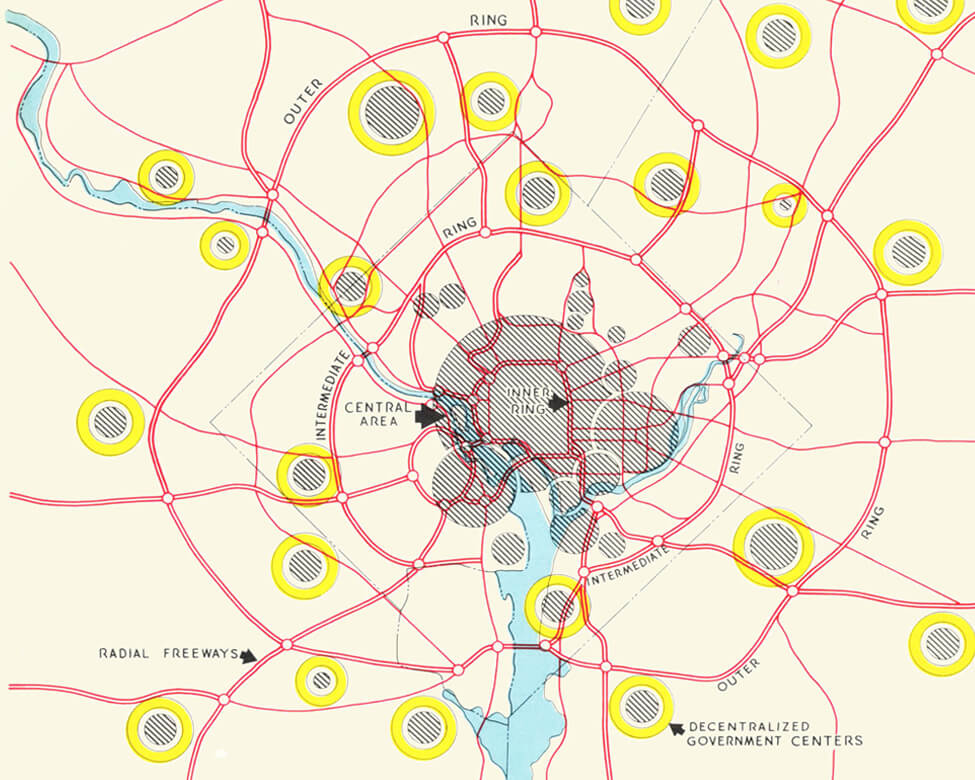

As many White Washingtonians departed the city for federally subsidized suburbs, NCPC’s 1950 comprehensive plan recommended building highways through and beyond the city. The plan anticipated the continued movement of residents and federal government offices out of Washington, but did not foresee the larger economic impact of “White flight.” Sparked by the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Washington’s April 1968 civil unrest was, in part, a response to urban disinvestment.

The big ideas in early comprehensive plans shaped the region’s growth while also creating long-lasting inequitable outcomes that today’s planners must address.

Reproduced

with permission of the DC Public Library, Star Collection © Washington Post

Professional planning pioneer Harland Bartholomew (1889–1989) oversaw the completion

of comprehensive plans for nearly 570 American cities. He chaired NCPC

from

1953 until 1960. Bartholomew was an early proponent of highway construction and

“slum

clearance” as tools for urban revitalization. During the Great Migration, millions

of

Black

southerners moved to urban centers across the United States. Here, he is seen

testifying

before Congress in 1955.

Reproduced

with permission of the DC Public Library, Star Collection © Washington Post

Professional planning pioneer Harland Bartholomew (1889–1989) oversaw the completion

of comprehensive plans for nearly 570 American cities. He chaired NCPC

from

1953 until 1960. Bartholomew was an early proponent of highway construction and

“slum

clearance” as tools for urban revitalization. During the Great Migration, millions

of

Black

southerners moved to urban centers across the United States. Here, he is seen

testifying

before Congress in 1955.

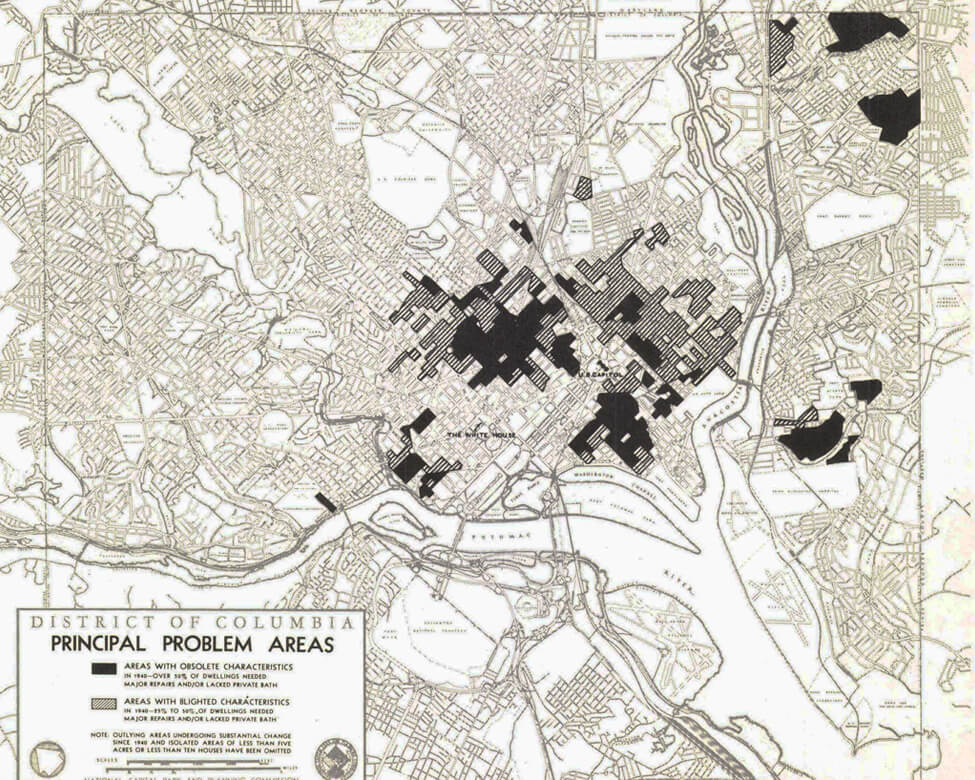

NCPC

Bartholomew’s city and highway plans contributed to racial segregation and the

frequent

displacement of Black communities. A map in NCPC’s 1950 comprehensive plan, produced by

Bartholomew’s firm, seen here, designated as “problem areas” many neighborhoods close to

downtown as well as Georgetown, Barry Farm, Marshall Heights, and Deanwood.

NCPC

Bartholomew’s city and highway plans contributed to racial segregation and the

frequent

displacement of Black communities. A map in NCPC’s 1950 comprehensive plan, produced by

Bartholomew’s firm, seen here, designated as “problem areas” many neighborhoods close to

downtown as well as Georgetown, Barry Farm, Marshall Heights, and Deanwood.

Courtesy DC Public Library,

The People’s Archive

Courtesy DC Public Library,

The People’s Archive

Mapping Segregation DC

NCPC

NCPC

Visit

Montgomery

Visit

Montgomery

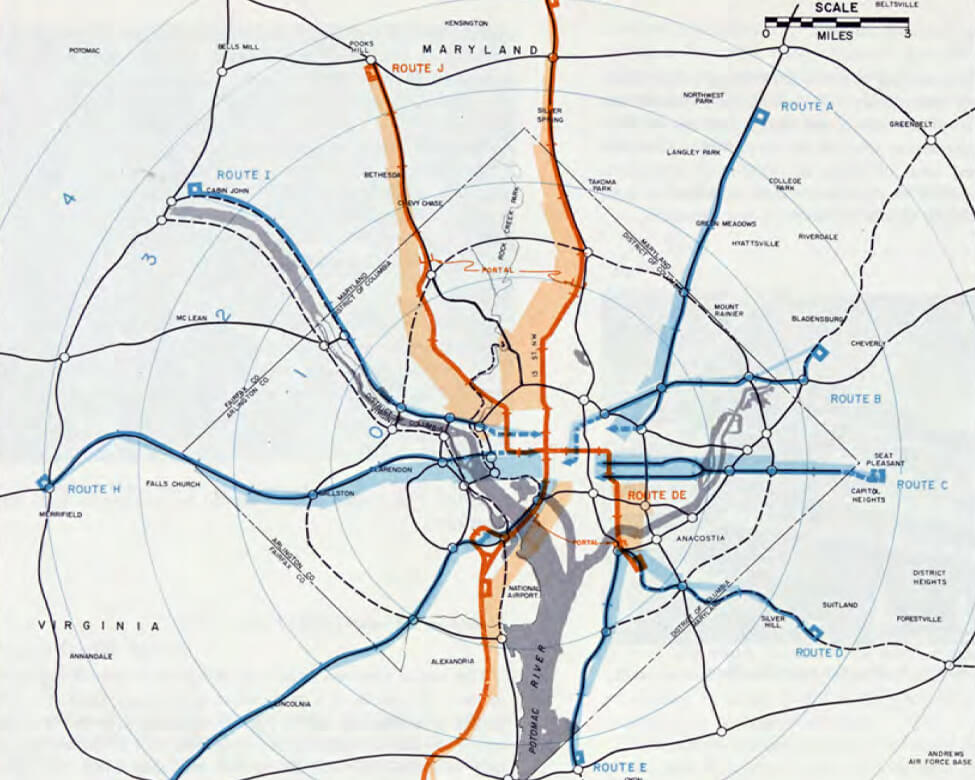

Transportation drives development patterns. Later NCPC plans adapted this concept, locating intensive development along highway “corridors” while preserving open space and encouraging less dense development in the “wedges” in between, as seen in this 1961 map. This idea is most fully realized in Montgomery County, Maryland. Other parts of the region have grown in more sprawling patterns.

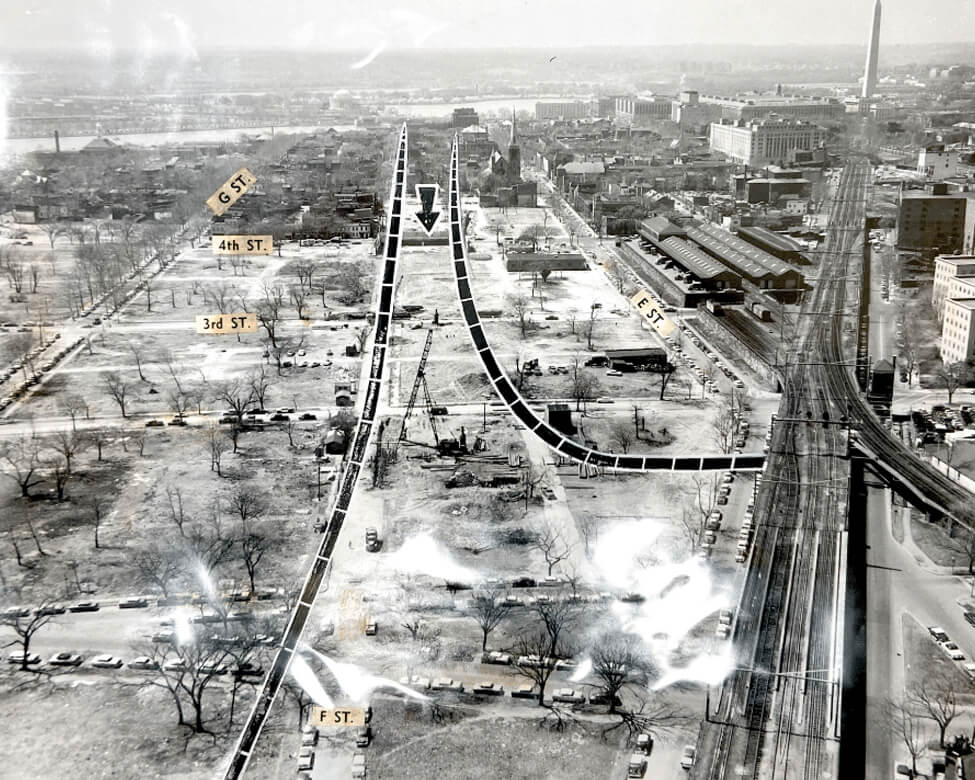

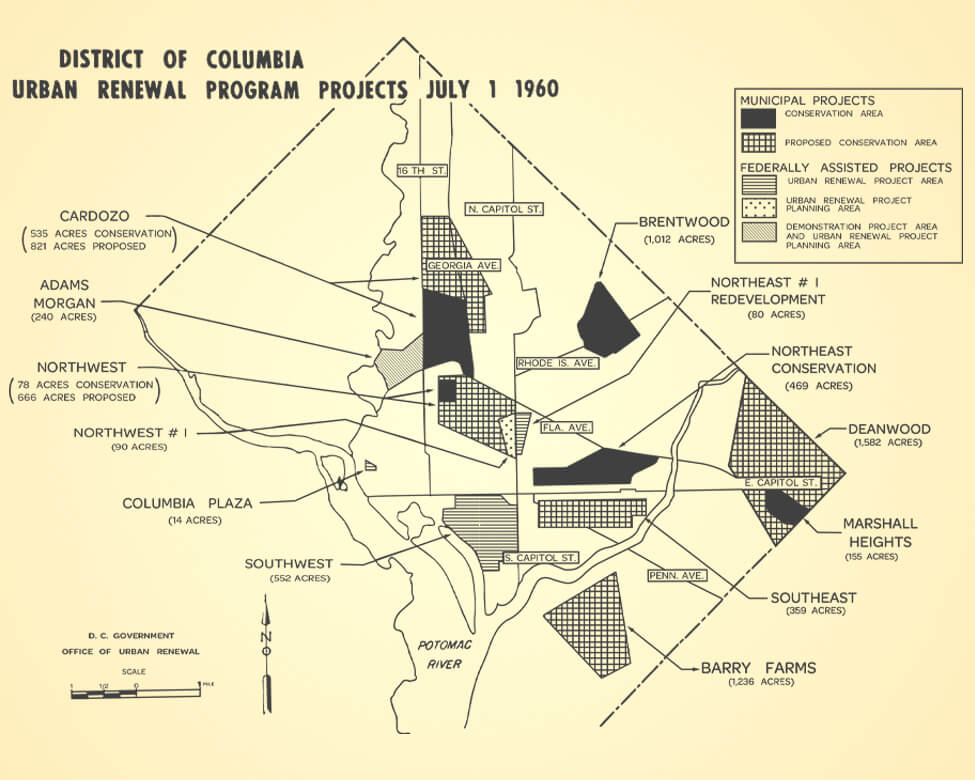

With the 1945 District of Columbia Redevelopment Act, Congress charged NCPC with devising proposals for rebuilding large swaths of the city. The new Redevelopment Land Agency (RLA) would oversee the work, which was referred to as “urban renewal.” Congressional advocates of urban renewal were eager to test the idea far from their own constituents.

Five years later, NCPC’s first comprehensive plan for Washington advanced Southwest as a pilot urban renewal project. Once realized, urban renewal in Southwest created a wholly new neighborhood as it simultaneously displaced thousands of people.

Until the 1950s, Southwest was home to poor and working-class, mostly Black families. NCPC planners debated whether to rehabilitate some of the old buildings or tear everything down and build anew. The Washington Post and other White business leaders pushed for the latter. In a 1954 case based on urban renewal in Southwest, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled as constitutional the government’s taking of people’s property, whether blighted or not, to be privately redeveloped for urban renewal.

In the end, most of the neighborhood was razed, and about 13,500 people and 1,500 businesses were displaced.

– Justice William O. Douglas, in Berman v. Parker, 1954

Almost none of the people who had lost their homes could afford the new housing in their old neighborhood.

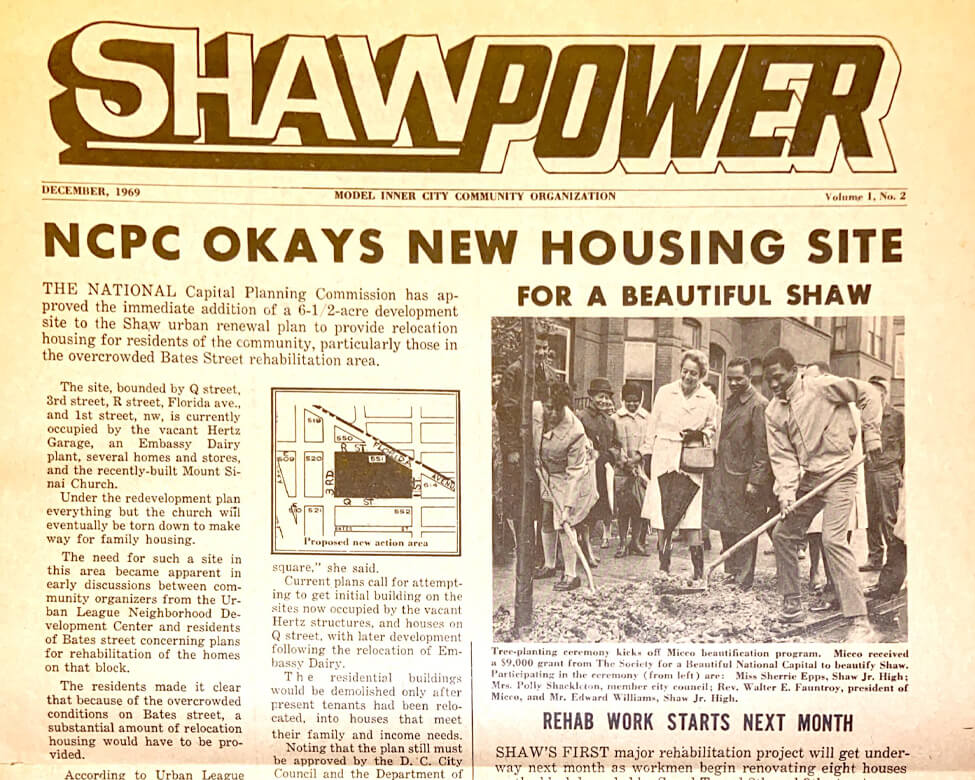

In 1969, Rev. Walter Fauntroy, at right, confers with architect Herbert McDonald and young Cedric Carter on plans for a block destroyed during the previous year’s civil unrest that would ultimately become the site of the Lincoln-Westmoreland Apartments. (Reproduced with permission of the DC Public Library, Star Collection © Washington Post)

This 1969 MICCO publication celebrates redevelopment work in Shaw. (All Souls Unitarian Archives)

Prior to serving as an NCPC Commissioner and the agency’s Executive Director, Reginald Griffith worked for MICCO. Check out his Massachusetts Institute of Technology graduate thesis exploring MICCO’s work with the community.

Adams Morgan

In the early 1960s, Adams Morgan residents worked with NCPC and others to look at less disruptive urban renewal approaches. Unable to find an option without major displacement of homes and businesses, including those in this 1977 photo of 18th Street, NW, NCPC dropped its renewal plans.

By the 1950s, the automobile had radically reshaped American cities, fostering expansion far beyond traditional downtowns. In 1959, NCPC and the National Capital Regional Planning Council prepared a regional transportation plan that recommended more than 300 miles of new roads.

“Gen Duke is stooge for the Highway Lobby … but citizens go for Mrs. Rowe!” Freeway opponents picket an NCPC meeting in 1966. Their signs refer to NCPC Chair Libby Rowe, DC Engineer Commissioner Charles Duke, and the first lady, Lady Bird Johnson.

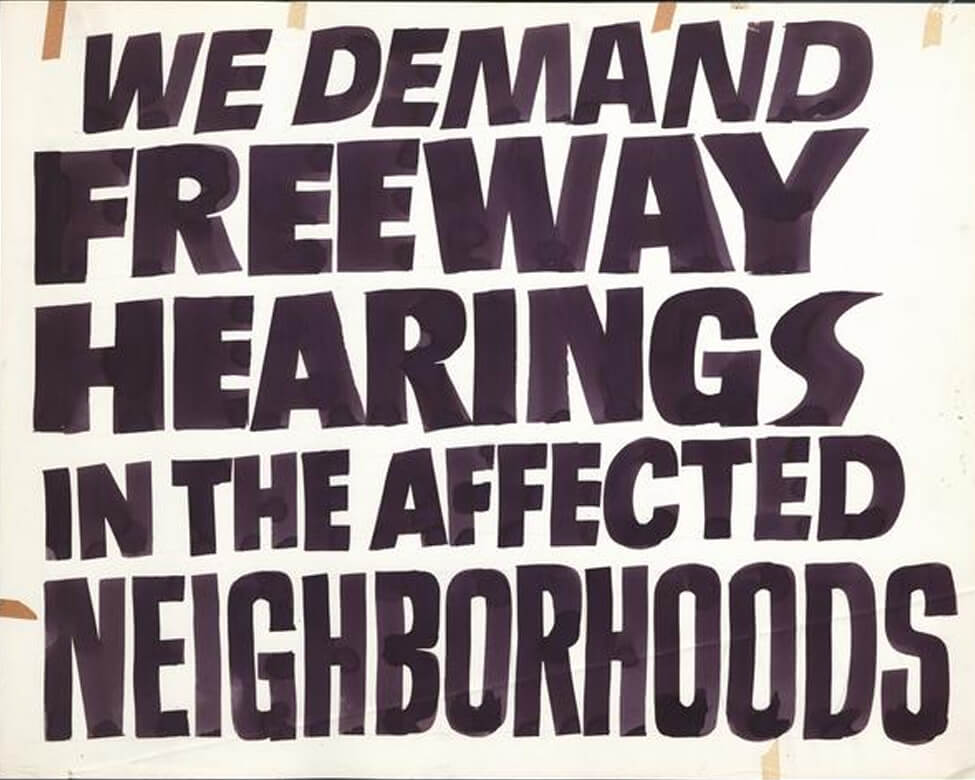

Civil rights leaders and neighborhood activists formed the Emergency Committee on the Transportation Crisis (ECTC) in the 1960s to oppose further highway construction. Pictured is an ECTC protest sign from 1965.

Residents of neighborhoods in the path of the proposed North Central Freeway, including Brookland and Takoma Park, picket outside the Commerce Department during a highway hearing in 1965.

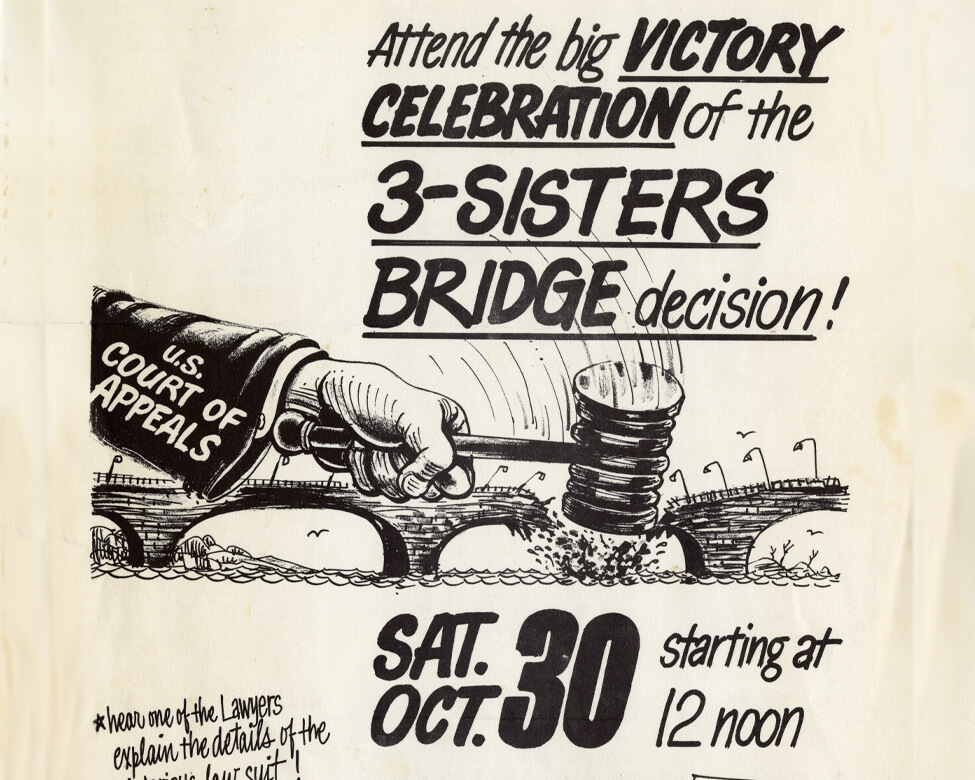

In 1971, anti-freeway activists celebrate a setback for the proposed Three Sisters Bridge over the Potomac River, to have been built up-river from Key Bridge as part of the Inner Loop project.

Reproduced with permission of

the DC Public Library, Star Collection © Washington Post

Reproduced with permission of

the DC Public Library, Star Collection © Washington Post

Libby Rowe (1912-1991), appointed in 1961 by President John F. Kennedy as NCPC’s first female commissioner, quickly rose to chair, serving until 1968. The native Washingtonian opposed further highway construction and urban renewal and championed a regional Metro system and historic preservation. She called the subway system “the salvation of the center of the city.” Here, Rowe is pictured in 1961 after she is sworn in as commissioner.

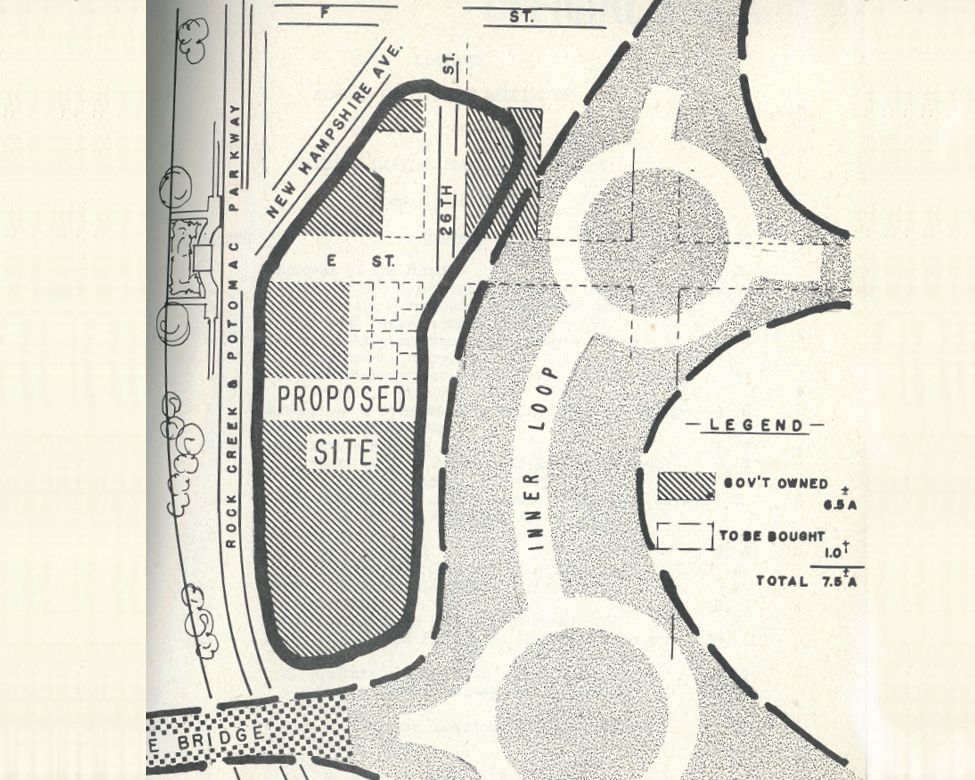

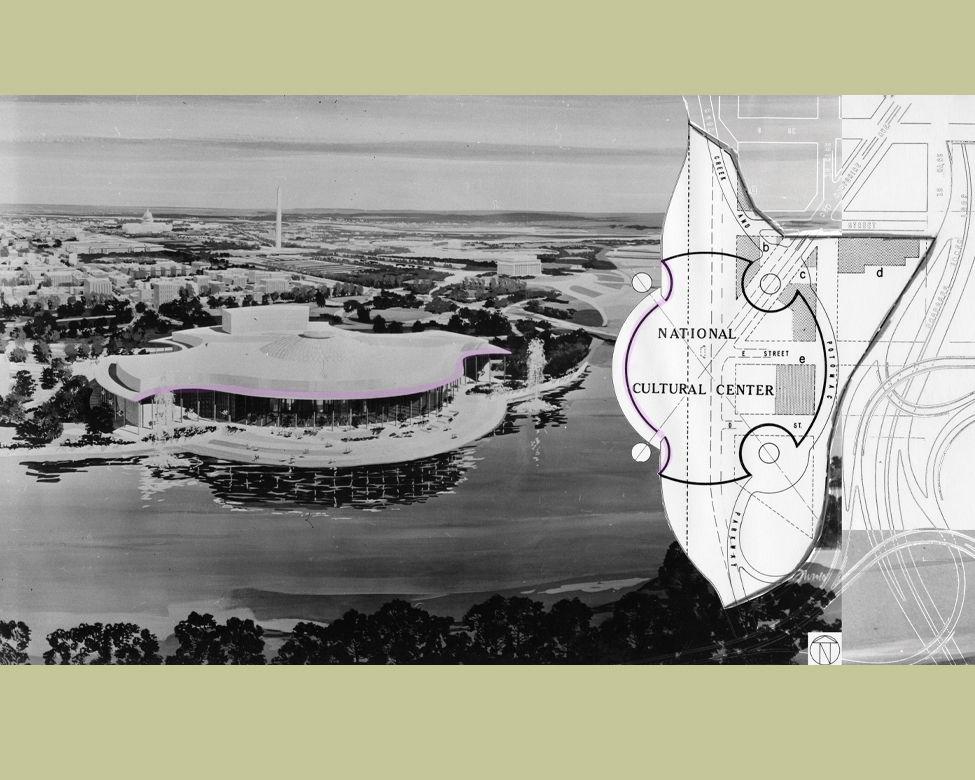

With freeway construction and urban renewal already underway in Southwest, planners considered the Foggy Bottom area more feasible. Federal ownership of much of the site, and its riverfront location, were additional selling points. NCPC acquired additional land and provided expert advice during the lengthy site selection and design process. Even as the project moved forward, there was criticism of the freeway “spaghetti” that separated the new center from the National Mall and adjoining neighborhoods.

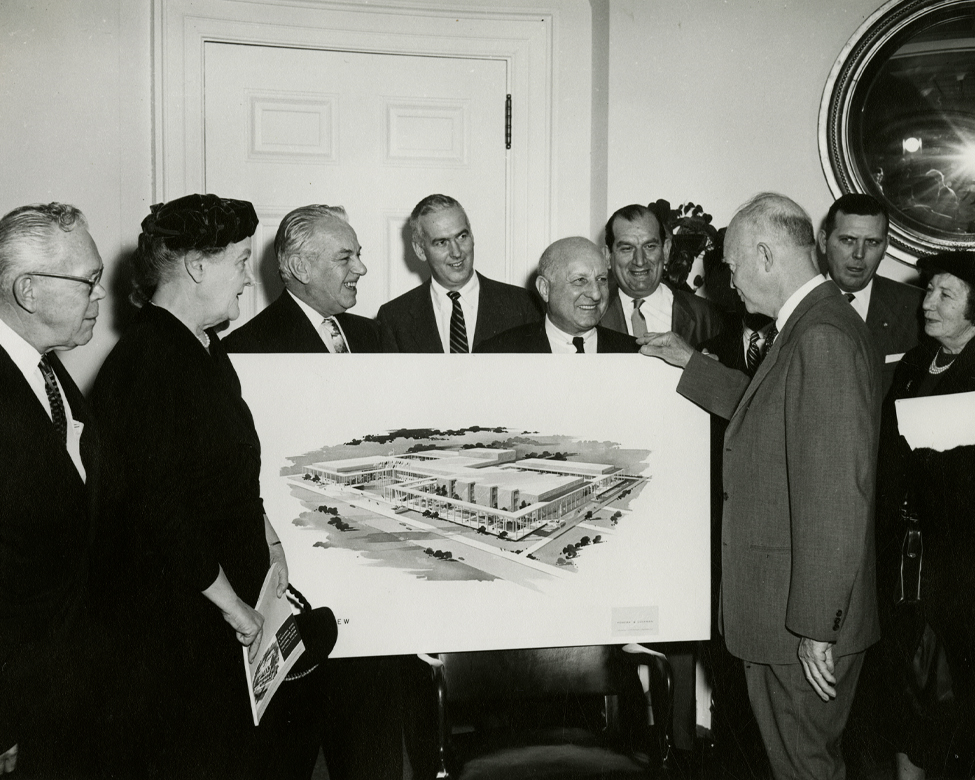

Multiple administrations supported the National Cultural Center, starting with President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Congress, with strong support from President Lyndon B. Johnson, decided to designate the center as a living memorial to President John F. Kennedy shortly after his 1963 assassination.

Courtesy of the Kennedy Center

Archives

Courtesy of the Kennedy Center

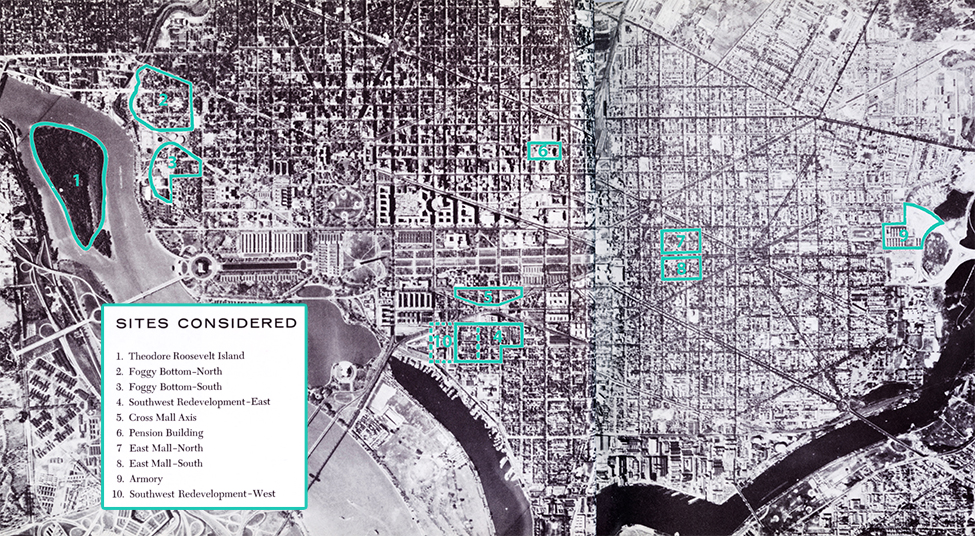

ArchivesThe District of Columbia Auditorium Commission’s 1957 report proposed possible locations (outlined in green) for what is now the Kennedy Center. The debate continued for years, with other locations proposed, including the site of today’s National Air and Space Museum.

– President John F. Kennedy, LOOK Magazine, 1962

Courtesy of the

Heurich House Museum

Courtesy of the

Heurich House Museum

NCPC

NCPC

Courtesy of the Kennedy Center

Archives

Courtesy of the Kennedy Center

Archives

Courtesy of the Kennedy

Center

Courtesy of the Kennedy

Center

Washington Monument

The REACH (opened 2019) expanded the Kennedy Center’s program space and established new connections to the riverfront.

Perkins Eastman - Urban

Design, Dariush Watercolors - Rendering

Perkins Eastman - Urban

Design, Dariush Watercolors - Rendering

John F.

Kennedy Presidential Library

First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy and project architect John Carl Warnecke at a press

preview of

the historic preservation and redevelopment plans for Lafayette Square in 1962.

John F.

Kennedy Presidential Library

First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy and project architect John Carl Warnecke at a press

preview of

the historic preservation and redevelopment plans for Lafayette Square in 1962.

Photograph

by Abbie Rowe, National Park Service

Libby Rowe, on the left, plants trees in the triangle park at 22nd Street and

Massachusetts Avenue, NW, across from the Cosmos Club in April 1966.

Photograph

by Abbie Rowe, National Park Service

Libby Rowe, on the left, plants trees in the triangle park at 22nd Street and

Massachusetts Avenue, NW, across from the Cosmos Club in April 1966.

Photograph by Joe

Getty

Photograph by Joe

Getty

"Don’t Tear It Down" members Lois Snyderman, Patricia Williams, and Karen Gordon are seen protesting here in 1979.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

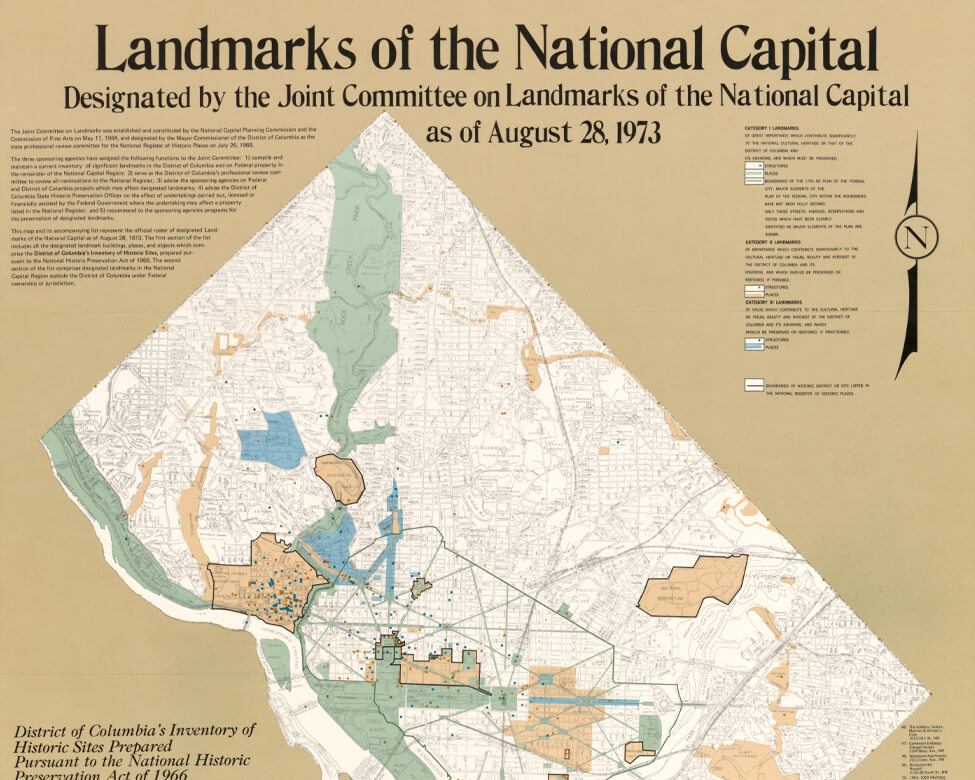

This 1973 map shows landmarks designated by the Joint Committee on Landmarks of the National Capital.

-

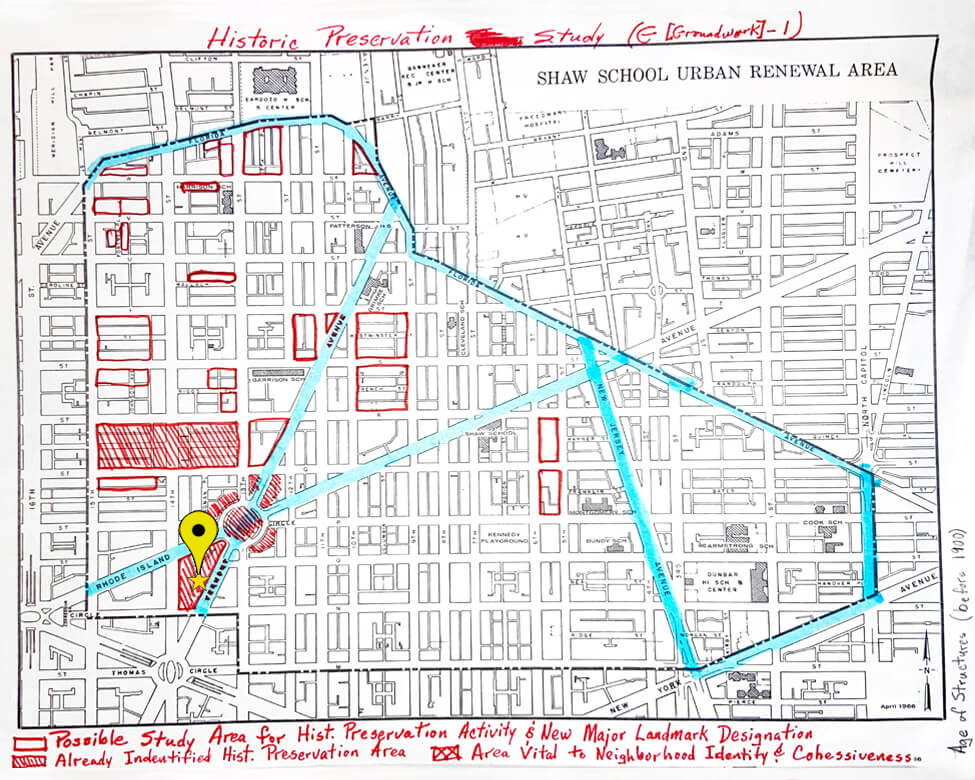

Shaw School

NCPC prepared this map while considering a pilot historic landmarks project in the Shaw School Urban Renewal Area. It includes the National Council of Negro Women headquarters and home of educator and activist Mary McLeod Bethune just southwest of Logan Circle, identified in the map. Because most designated sites were grand buildings associated with White architects and historical figures, the Afro-American Bicentennial Commission formed in 1970 to preserve sites important to the nation’s Black history.

-

Bethune House

In 1974, the Afro-American Bicentennial Commission nominated the Bethune House at 1318 Vermont Avenue, NW for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places, but the site was not added until in 1982.

NCPC continued to advance federal interests and review development on federally controlled land in Washington — about 40 percent of the city — and the surrounding region. The District of Columbia government took over the task of planning in the rest of the city, addressing housing, local economic development, land use, and other community needs.

NCPC

NCPC

Citizens meet in the District building in 1967 to voice their opposition to highway construction.

Reproduced with permission of

the DC Public Library, Star Collection © Washington Post

Reproduced with permission of

the DC Public Library, Star Collection © Washington Post

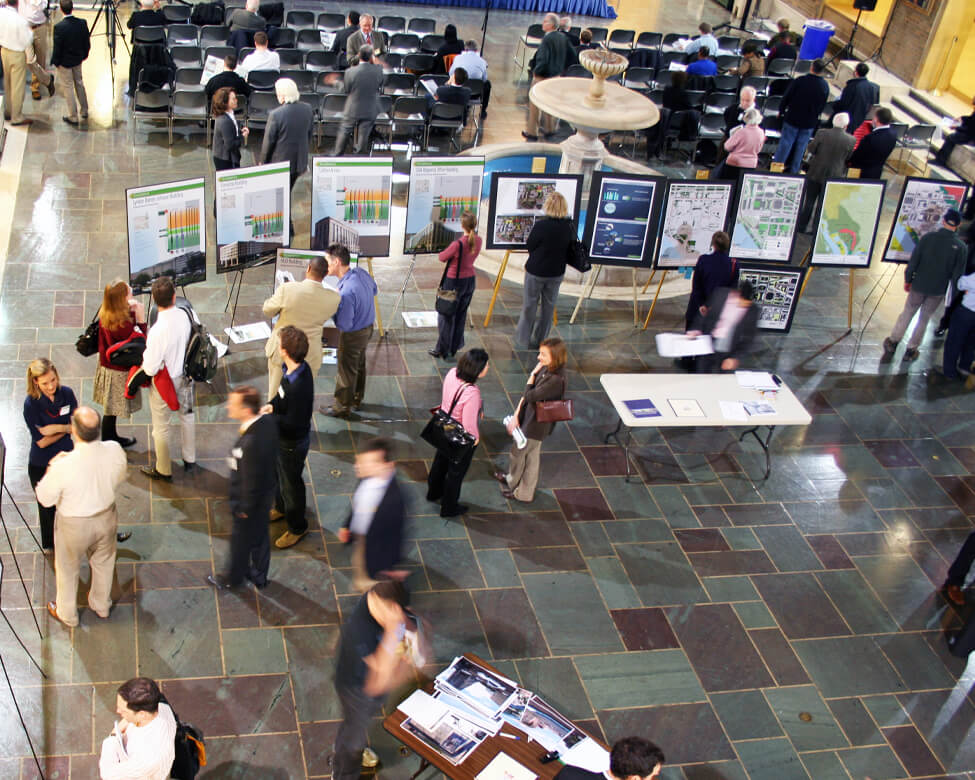

Today, public participation is a key element of federal and District planning. The public gather at a 2012 NCPC hearing on the SW Ecodistrict Initiative’s efforts to transform the isolated federal precinct into a walkable, mixed-use area.

NCPC

NCPC

The Comprehensive Plan

NCPC and the DC Office of Planning jointly develop a comprehensive plan that

guides federal and District development. Both agencies are incorporating

policies that recognize unjust past planning practices and seek to create

more equitable outcomes today.

Federal Elements

District Elements

NCPC

NCPC

Pennsylvania Avenue

Championed by Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, the Pennsylvania Avenue

Development Corporation would plan for and implement the redevelopment of

the avenue between the U.S. Capitol and the White House in the early 1970s.

The avenue is home to special events and First Amendment

demonstrations that attract local and national audiences. Today, NCPC leads

a partnership of federal and District agencies to revitalize this nationally

important public space that is also key to downtown’s post-pandemic

recovery.

Penn Ave Initiative

Here are questions about Washington’s future that NCPC is tackling.

Beyond Granite

Steve Weinik for

Beyond Granite

Steve Weinik for

Beyond Granite

Beyond Granite

Derrick Adams’s America’s Playground: DC is a fully operational playground that reflects on legacies of leisure, racial division, and transformation in Washington and beyond.

Public Space Security

NCPC

NCPC

Washington Monument

This Laurie Olin design, installed in 2005, provides graceful pathways leading to the Washington Monument while providing a barrier from vehicular attacks.

Federal Workplace Study

Golden Triangle

Business District

Golden Triangle

Business District

Transformations

Downtowns are responding to changing ideas about where to live, work, and play. Here, pandemic-inspired “streateries” expand dining options.

NoMa Business

Improvement District

NoMa Business

Improvement District

ATF Headquarters

The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives Headquarters, designed by Moshe Safdie and completed in 2008, anchors redevelopment in the NoMa neighborhood and an infill Red Line Metro station.

- What kind of memorial would you like to see?

- How can we make our public spaces both safe and welcoming?

- How would you like to see the capital region grow?

- How can federal development be part of communities?

- What did you find interesting about this exhibit?

I’d like to see a memorial to farmers and agricultural laborers and their importance to feeding society.

Public spaces can be safe and welcoming with lively spaces nearby, plenty of trees, seating, lighting, and fun activities. People should feel like they belong in those spaces!

I’d like to see more investment east of the Anacostia River!

Federal agencies should listen and communicate with local residents, not only once, but on an ongoing basis. Engaging with the community should be a consistent practice.

What kind of memorial would you like to see?

* One for LGBTQ people victimized by discrimination/violence, and one for workers killed/injured due to their work conditions

How can we make our public spaces both safe and welcoming?

* Put unarmed people on t. . .he streets as security observers / walking companions to reduce desolation and fear in depopulated areas; install more public bathrooms, (working) water fountains, and benches

How would you like to see the capital region grow?

* With high density, public transit, bike lanes, abundant housing at multiple price points

How can federal development be part of communities?

* DC statehood

What did you find interesting about this exhibit?

* The photos and maps are fascinating to examine!

Show more

Great exhibit! I'd like to see a DC that has more considerations for micromobility, like bikeshare and scooters.

Memorialize the kidnapped and trafficked Africans who were sold into slavery on the national mall with a monument where the slave pens were. Memorialize every neighborhood where thriving Black communities were wiped out especially in NW and SW DC

I would like to see better designed streets, more protected bike lanes, greater Metro coverage and even tram lines within DC..and please no gadgetbahns.

What I found most interesting about this exhibit is that planners, including the NCPC, can be wrong with detrimental consequences. The highways that were built through the center of DC were revolted against, such that the Inner Loop was never completed and no one would ever propo. . .se it today.

Show more

I think that some Federal department headquarters should be relocated to outside of DC to be closer to the places where their actions mean more like agriculture to the Midwest or Transportation to Atlanta or Detroit.

But if they do move I think one of the office are. . .as for the headquarters should be demolished and a Cabinet Building be built in its place to house DC offices for department heads and bedrooms if they have to stay for a extended period after they are done moving the departments to be spread out in different parts of the states, maybe a beaux arts style for the building and a public area with statues of the most famous cabinet positions held at each department.

Show more